Talent management increases the output of high potentials (not)

Companies investing in talent management do better than those that don’t. Several studies have already proven this apparently macro-economic correlation (Bethke-Langenegger et al., 2011).

Two fascinating recent studies have tried to explain the effects of talent management programmes on the micro-level. In particular, the allocation of talented employees to different groups or categories and the tools and processes used for that purpose were explored with a view to the perceived fairness and impact on satisfaction and commitment in the study “Talent management and organisational justice: employee reactions to high potential identification”, produced by a group of researchers from Louvain and Brussels (Gelens et al., 2014).

The study “Linking high performance organizational culture and talent management: satisfaction/motivation and organizational commitment as mediators“ published by Kontoghiorghes (2015) explores the impact of a high-performance culture on how effective talent management is and how satisfied and motivated talented employees are. It does so by following two high-performance organizations from different industries and countries, both of which share a readiness for change, commitment to quality management, knowledge, growth, ethical practice, and development opportunities.

The study confirmed all assumptions suggesting that a high performance culture has a strong effect on individual talents and on the effectiveness of the talent management process (in the sense of attracting and retaining talented employees). The conclusion is that a “change-driven culture” in particular is appreciated strongly by designated talents for the much greater development opportunities it offers. Respect and integrity are the strongest drivers for their motivation and satisfaction, leading to organizational commitment and, in turn, promoting the effectiveness of talent management.

The study by Gelens et al. reveals how being identified as a high potential affects people’s sense of satisfaction and commitment to their work. The analysis is based on the assumption that management decisions are intricately linked with the subjective perceptions and reactions of the people affected. Employees will always give as much as they can hope to receive back (Social Exchange Theory, Blau 1964).

The results imply that being designated as a high potential has an impact on the satisfaction and motivation of an employee. An impact that is positive – but just as long as we ignore the other side of the coin, that is, how the other people, the ones not named high potentials, are discouraged by it. The studies also show us: The immediate effect is empirically virtually unrecognizable; it needs the mediating variable “perceived fairness of the allocation” to show strong correlation. The researchers are clear about what this means: The direct effect of employees being earmarked as senior high potentials is marginal. The designated talented employees, however, pay very close attention to whether the selection is fair to them. If that is the case, they will be far more satisfied. Their actual motivation for their work will, however, only be affected if they also consider the process itself to be very fair. If the fairness of the process is just considered average, the difference in motivation between high potentials and other employees already disappears.

Both studies show that a fair, respectful, and change-oriented culture of work, one that expresses respect and integrity, has a far greater impact on people’s satisfaction, motivation, and work ethics than any sophisticated talent processes or definition of talent categories. Talent management lives off the commitment of the talented people included in it, and this commitment is promoted by the given culture, not by any talent tools.

We can see very clearly that talent management is essential not an objective process, but a subjective social intervention whose success, especially when ‘workforce differentiation’ is concerned, depends substantially on how fair the process and its results appear to be.

The studies draw our attention to an essential, but too often neglected lever of sustainable talent management:

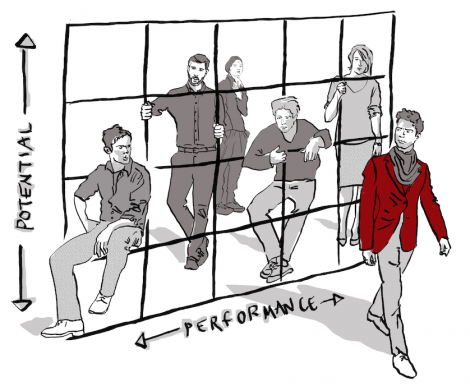

The end product of the process should not be a simple portfolio, like the classic 9-box grid. Despite all of its deceptive objectivity, such a blanket allocation of people to fixed talent categories offers virtually no added value in the sense of making them more motivated or committed to their work.

We believe effective talent management should change its focus:

- Intensive confrontation on the part of HR with the corporate (departmental) strategies and definition of a sophisticated target vision for what type of workforce the company wants

- Forming a positive organizational culture that attracts and retains talented people feeding that target vision

- Aligning the tools and process with the needs of the people affected by it: Employee experience design methods allow us to improve how the HR tools in action are perceived and whether they are accepted by the people at stake

Sources